The Perennial City?

by Michael Djordjevitch

On June 17th we had closed the journal entry with a tantalizing image of the sixteenth century persisting into the twentieth.

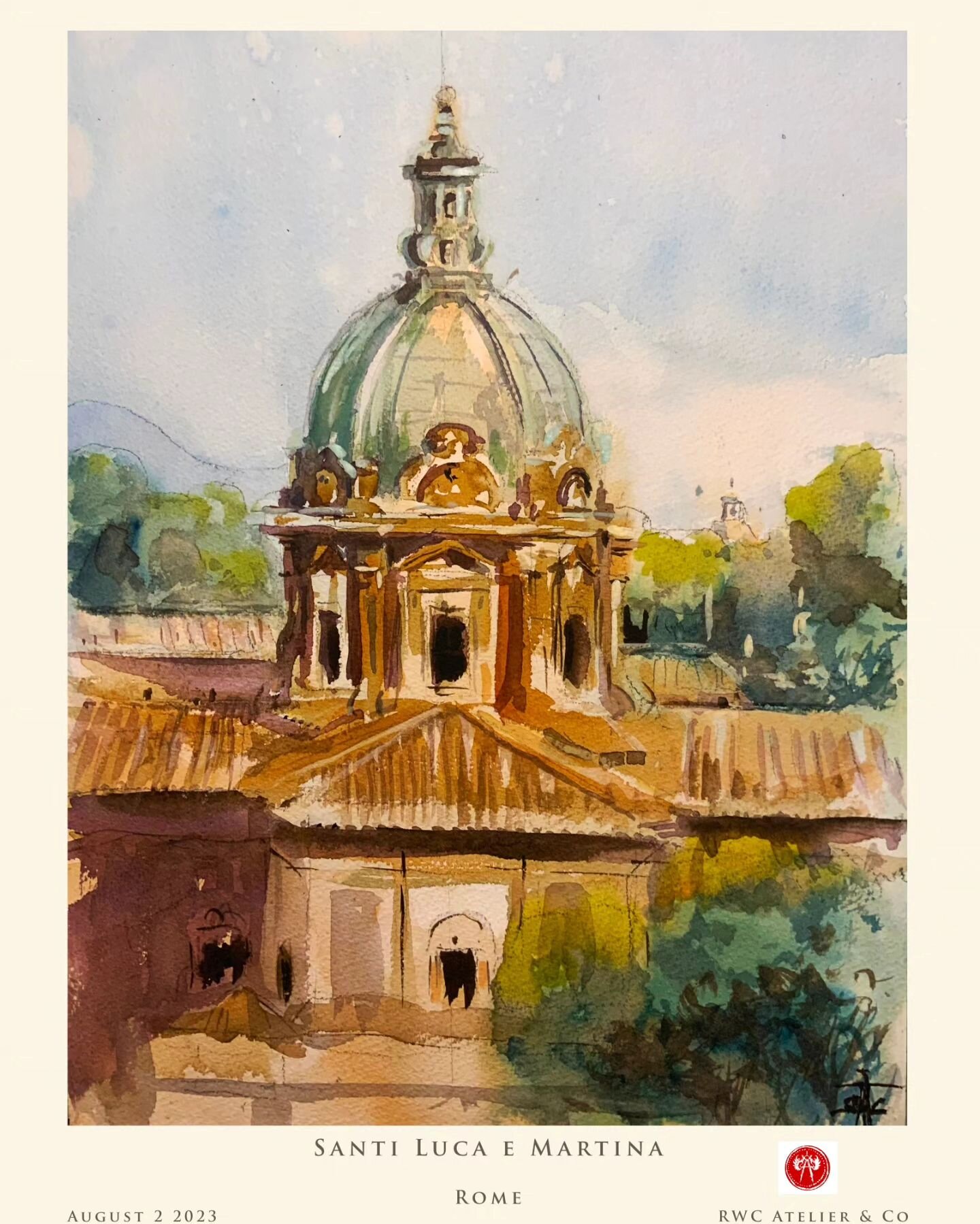

Now, looking out from within that portico, Pistoia's Loggia dei Mercanti, at the city around it, we take part in an urban experience that goes very far back, all the way to Ancient Rome and Greece.

Sadly though, everything that we see here, thanks to this postcard image, is no more, having been ravaged first by the various “improvements” of modern so called urbanism in the 1930s, and then by bombs during the Second World war.

And yet, it is for the very experiences conjured by this haunting image that millions upon millions trek to Italy every year.

Should it, then, even raise an eyebrow, that this freestanding Loggia in Pistoia (seen below from without), following upon the tradition of works such as Florence’s Loggia dei Lanzi, and much before that, the Ancient Greek Stoa, is also a twentieth century building ?

As we also saw with Pistoia’s Ospedale (Post of July 17), here the early twentieth century architect employed a prominent sculpted frieze, the most striking feature of his monument and the embodyment of its particular story. Then, to offset what would have been an otherwise top-heavy composition, and to help negotiate the site’s significant slope, he lifted his columns on compact pedestals, perhaps inspired by those gracing Assisi’s elegant first century B.C. Roman Temple:

The Loggia dei Mercanti’s round disks (tondi) between the arches are, however, more than just an occasion for heraldry and a supplement to the monument’s figural narrative. They also overtly bring to mind the prototype of all these Loggias, Brunelleschi's Ospedale degli Innocenti in Florence, and the first all’ antica work of architecture of the emerging fifteenth century Renaissance.

But, before we turn to the parent tondi by way of returning to Brunelleschi's loggia, let us pause at this miraculously well preserved ancient facade in Assisi to reflect on this puzzle. When Brunelleschi's contemporaries looked at his loggia, they saw not just an allusion to, but a full manifestation of an Ancient Roman Portico, such as the one above. Unlike us, they could see beyond the particulars of a historical style to the type-form of what would in the coming decades come to be called the Orders of Architecture.

Today, the outer face of Brunelleschi's building is enlivened through a set of prominent sculpted ornaments, one above each column: those memorable ceramic infants in swaddling cloths against a blue ground, no two of which are alike. Originally, each tondo had been left an empty concavity. Then, around 1490 Andrea della Robbia (1435-1525) was asked by the Ospedale to fill them with relief sculptures of infants.

Source

Did Brunelleschi originally intend such an embellishment of his building, these tondi ornamented with virtually monochrome ceramic sculptures in relief, but then after this --- nothing more? Simply because we are so used to seeing the monument as it is today, this familiarity, in and of itself, offers no evidence for what might have been originally intended. Our anachronistic assumptions are, to be blunt, a huge stumbling block.

Fortunately, a considerable body of evidence survives concerning the building history of this work and who was in charge at each phase. Through this, we learn that work on the building had begun in 1419, and that by 1427, when Brunelleschi left the project and Francesco della Luna took over, only the colonnade proper with its vaults had been built.

The second story was constructed more than a decade later. In the interim, the building was expanded by one bay to its left as a result its internal plan being modified. The body of the Ospedale was largely complete by 1445 when it was formally inaugurated. Brunelleschi died on April 15th, 1446. The institution’s Chapel was finished and consecrated a few years later. The elaborate central door and its balancing niches at either end of the colonnade were only added in the early 1660’s.

The first image below shows the state of the building in 1424, the date Brunelleschi ceased supervising the construction on a regular basis. The second shows the project in 1427, when Francesco della Luna took over.

Eugenio Battisti, Filippo Brunelleschi, Phaidon Press, 2002

On the face of it, this documentation would seem to indicate that we cannot really call this building Brunelleschi's, as, apart from the columns and their associated capitals, imposts, architraves, arches and vaults, the rest of the work, that is, the overall appearance of the monument as a whole, is the work of other hands, and minds.

And there things would remain, were it not for one rare piece of evidence, a biography by a contemporary, The Life of Brunelleschi, by Antonio Manetti (1423 - 1497). A reasonable degree of confidence can be ascribed to this witness, as its author was personally acquainted with Brunelleschi, and also had direct access to documents, drawings and models which we no longer possess.

Manetti describes having carefully studied a surviving drawing of the design for the facade of the Ospedale in Brunelleschi's hand. He then observes that one of the several deficits of the facade as he knew it in the late fourteen hundreds was the absence of small pilasters between each of the windows, and the lack of double pilasters above the large ground story pilasters at each end of the colonnade.

Eugenio Battisti, Filippo Brunelleschi, Phaidon Press, 2012

This brings us to the first of our final three images, and some reflections.

Here, at eye level, on Ghiberti’s masterpiece, which Michelangelo would justly name “the Gates of Paradise,” we are confronted with a curvilinear image of Brunelleschi's great Loggia. Though not immediately self-evident were one not aware of Manetti’s witness, nonetheless, this image strongly supports Manetti (as we see pilasters between the windows on the second story), and raises the larger question of, in what other ways was Ghiberti influenced by his rival.

If we recall that Brunelleschi was recognised in his own time as the first person since antiquity to realize perspectival realism, that is, spatial coherence, in painting (which he then showed his contemporaries how to achieve themselves through his demonstration painting of Florence’s Baptistry, circa 1414), we might then take note, that what Ghiberti is giving us, here, starting in 1425, are spatially coherent paintings, albeit by way of low relief sculpture in gilded bronze.

Source

Alberti in 1435 would document the geometric basis of Brunelleschi’s pioneering work in book one of the first edition of his treatise on the art of painting, De Pictura.

Having now ranged over a number of works of art mainly of the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries in these past months, what might we conclude regarding Brunelleschi's overall artistic intentions with respect to his Ospedale?

First, as it is highly unlikely that the tondi were meant to be empty; Andrea della Robbia’s infants there are an inspired contribution to the ensemble, giving iconic/symbolic voice to the institution. Recently, a number of polychrome glazed terracotta reliefs and statues have been identified as belonging to Brunelleschi's oeuvre, making it even more likely that Andrea was realising our architect’s intentions here.

Second, with the windows on the attic story framed between pilasters (thanks to Manetti’s witness), a set of stable pictorial fields now become available. We need only to look at another painter-architect’s work, that of Baldassare Peruzzi’s at the Farnesina in Rome, to see how these might have been filled. Below is a sketch (now in the MET’s collection) of Peruzzi’s design for the interstices of the facade as Peruzzi himself had realised them. Today's empty fields there are the product of much more recent times.

Source

Third, let us now turn our attention to the frieze register of the Ospedale of the Innocents. Here the Ospedale in Pistoia offers a promising parallel: a figural narrative, to be realised in Florence in either sgraffito, fresco, or glazed terracotta.

However, given the present balance between the pietra serena elements and the stuccoed fields they frame, and, given that, as they stand these relations are very finely judged, a monochrome composition in sgraffito, or fresco is the likeliest.

Our present open frieze in the context of this facade operates as both a frieze and also an attic/parapet; thus, it formally creates a nuanced transition between the upper and lower registers of our facade that combines aspects of each, through what is called ellison. It is therefore highly unlikely that the frieze was intended to be solid, that is, executed throughout in pietra serena.

Today, at either corner of this facade within the register of the frieze can be found a short stretch of multiple strigils in pietra serena (this, a popular motif, which can be found on many Roman Sarcophagi). It is most improbable that this strigilation was intended to stretch continuously across the facade, as it would have visually split the building in two, the opposite of elision. Perhaps this strigilation was an idea of Francesco della Luna’s, or one of his successors, or, more likely, these short stretches were solely intended to punctuate and strengthen the ends of the frieze register.

In the lower story we see (in the detail below) the upper part of the larger order corinthian pilaster which frames the building’s colonnades. Above it, and above the frieze, in that empty space is where the paired second story pilasters would have been placed.

Let us now return to where we had begun a number of essays ago (on July 10), and again bring to mind the interior of the Ospedale’s colonnade and those pendentive vaults colorfully realized. Given how they presently operate, strengthening the experience of key thresholds, they are far from being in conflict with Brunelleschi’s overall design. Being consonant with all that we have explored and discovered, they too should be added to Brunelleschi's possible palette.

It is important not to get too taken in by the presentation of our artist in popular books such as Ross King’s Brunelleschi’s Dome. Useful as this book is as an introduction to the project for the dome, also to the man and his times, in foregrounding the builder and the engineer, the book unfortunately also contributes to our collective overlooking of Brunelleschi the epoch-changing artist.

Brunelleschi began as a sculptor, in metal, in ceramic and in marble, and in forms large and small. He then became the painter who first achieved coherent spatial representation, perspective, and introduced his times to the charms and challenges of spatial realism. Then, in middle age he became the architect who reintroduced the Ancient Roman Manner, the all’ antica, and the builder engineer who surpassed the Romans in that realm. However, let us not, for all his significant later achievements, forget The Artist.

Brunelleschi’s last documented work was a Pulpit for Santa Maria Novella, begun in 1443, and competed by Brunelleschi's adopted son, Andrea Cavalcanti, who was a sculptor, and had worked on a number of his father’s projects.

As a rare surviving and uncontroversial complete work by Brunelleschi, the testimony of this pulpit should be carefully considered (see the posting of July 29 as well). So, what then do we encounter here?: low relief figural scenes, pictures, framed by architectural elements, themselves supported by multiple architectural elements; a wealth of architectural ornament, and yet, the whole --- serenely balanced.

Among the Florentine artists who followed him, Michelangelo stands out as being the most vocal in his admiration of Brunelleschi. He also stands out, along with Alberti, as being the most attentive, and deepest of his students (To be Continued ...).