Here are some in Milan--Ancient Mediolanum--or rather their remaining foundations:

Their plan:

And an imagined reconstruction, by the talented and prolific Francesco Corni, with the remaining foundation walls shown in the foreground:

Here is the suite in what’s left of its original context, at the top in red with the other archaeological remains of the palace:

As in Rome the palace occupied its own special precinct, which like that on the Palatine Hill in Rome overlooked a racing circus, where the emperor could see and be seen by the Roman public:

(this and other line drawings here also by Corni)

Likely the palace in Mediolanum was built for the Roman emperor Maximan in the late 3rd Century AD, when the city became one of four new capitals of the Tetrarchy inaugurated by Diocletian. All were located on the empire’s periphery near its northern and eastern boundaries which were increasingly vulnerable to barbarian incursion.

And how, given that so much of their immediate context is missing, do we know Maximian’s private apartments were the very scanty remains we see today? Their shape and configuration are familiar from earlier palace architecture, but what really tells is their character as a self-contained and highly ordered “world within the world” of the larger palace complex, just as this complex itself constituted a self-contained and idealized world within the real world of the city. In the emperor’s private suite this theme is restated in its most compact and elaborate form.

We recognize the same theme at Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli outside Rome. At one end of the so-called Piazza d’Oro were likely the private apartments of that emperor (at left above), and there we find the basic arrangement later repeated in Milan. A major domed space with a central fountain, likely beneath an oculus, was flanked by a pair of suites arranged around their own small open courtyards (shown roofed by mistake in the section drawing). These smaller suites reprised the larger arrangement, with a central salon or day room between a pair of two-room suites, each with a vestibulum preceding the cubiculum, or bedroom proper, which was also accessible by a separate service door. Lavatories were back on the other side of the private courtyard, tucked between it and the major domed room.

Hadrian’s private apartments like the villa they belong to likely represent the imperial palace--at least in its villa incarnation--on its most lavish scale, which is appropriate for the ruler of the Roman Empire at its height, himself an architect and the likely designer of his own villa as well as the Pantheon in Rome, that greatest domed space open to the sky.

Closer to Maximian’s time we find the same arrangements in a much better state of preservation at the villa in Piazza Armerina, Sicily, which may in fact have been the tetrarch’s country retreat from Mediolanum.

Here at one end of a large peristyle courtyard we find a long transverse gallery (28) with a major hall beyond (43), flanked by two suites of private apartments. The more elaborate of these (37-41) were again the emperor’s or the imperial family’s private apartments, with again a pair of two-room sleeping suites on either side of a covered fountain court, this one semicircular. On axis beyond is an apsed day room, a smaller version of the audience hall down the corridor. Again the private suite reprises and repeats larger patterns in more compact, elaborated form.

Now we can return to the private apartments in Mediolanum, which we recognize as an expanded version of those at Piazza Armerina.

We have the same transverse gallery, with the same fountain court and apsed hall beyond it on axis. Here the fully circular hall allows for three private suites, each with salons flanked by two cubicula, the largest of these, on axis with the fountain court and gallery presumably belonging to the emperor.

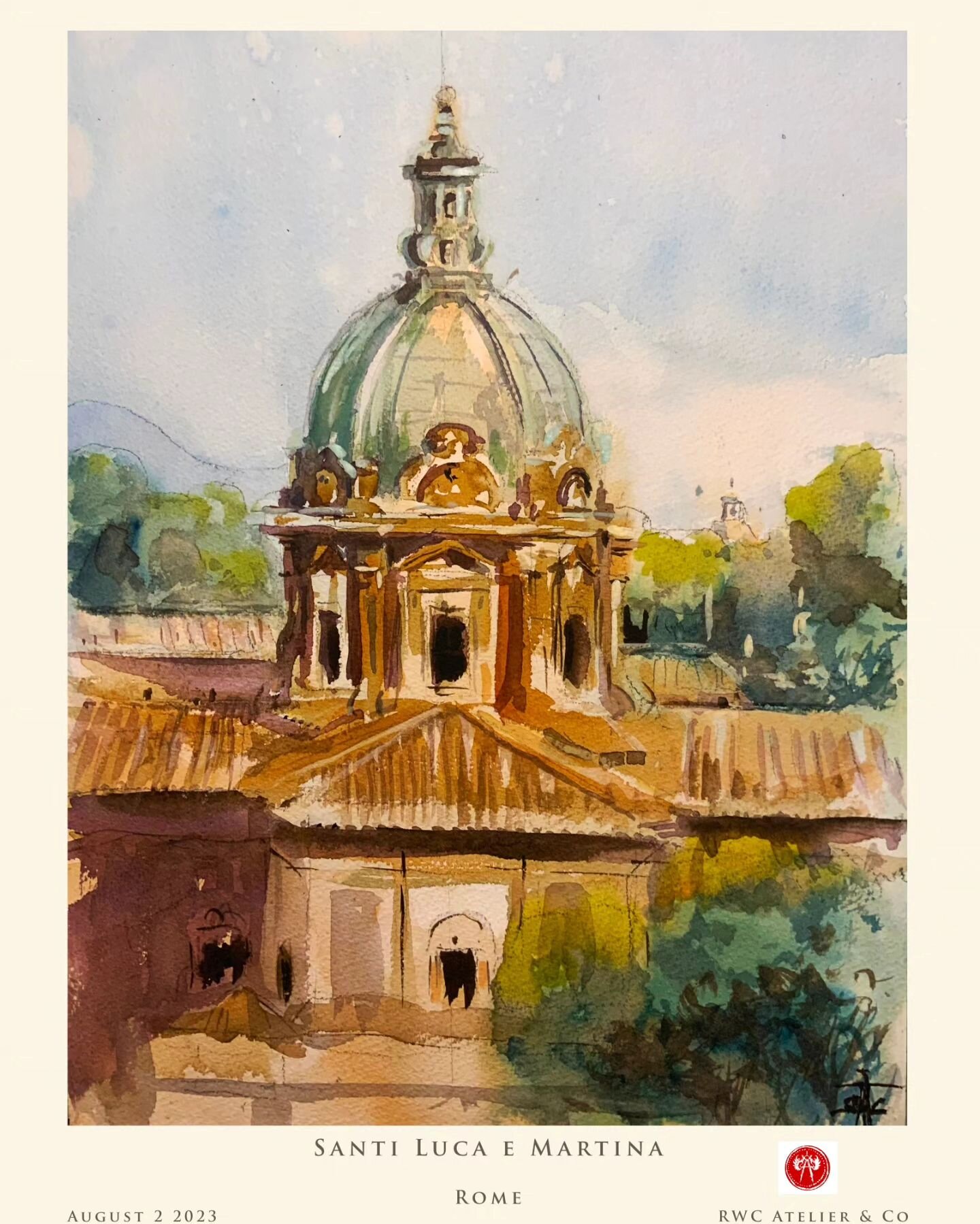

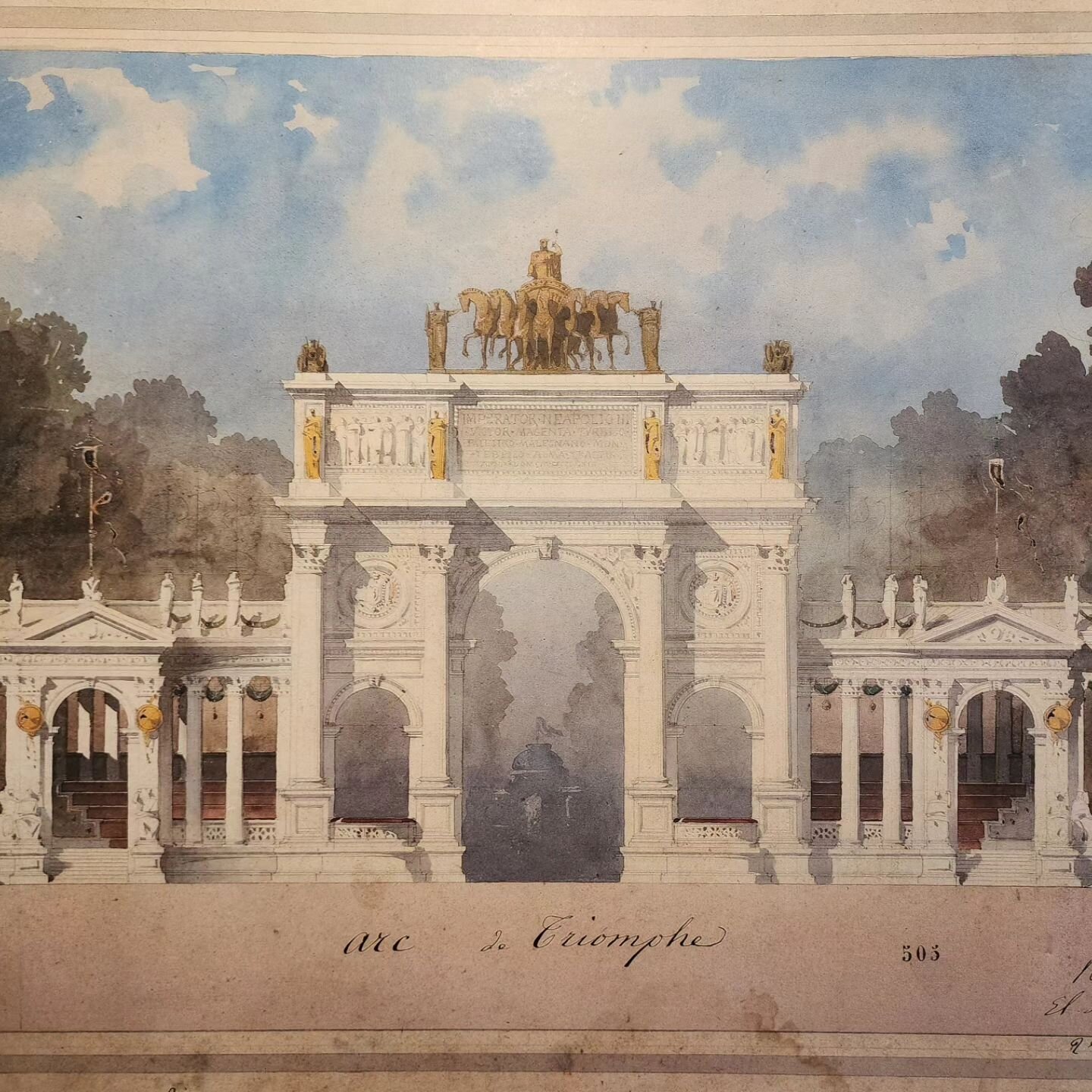

And what did it feel like to inhabit this centralized and idealized world within the world? For this even imaginative reconstructions like Sr. Corni’s or the French architects who reconstructed Hadrian’s Villa are not enough. We have to imagine those spaces not from above or outside but from the inside, as they were experienced, as settings for both ritual and routine.

This painting of a Roman interior by the Italian artist Ettore Forti gives some idea of the experience of a private suite in a Roman palace. It's a long way indeed from what remains. How far, though, was that ancient reality from this one?

--- Sam Roche