by Michael Djordjevitch

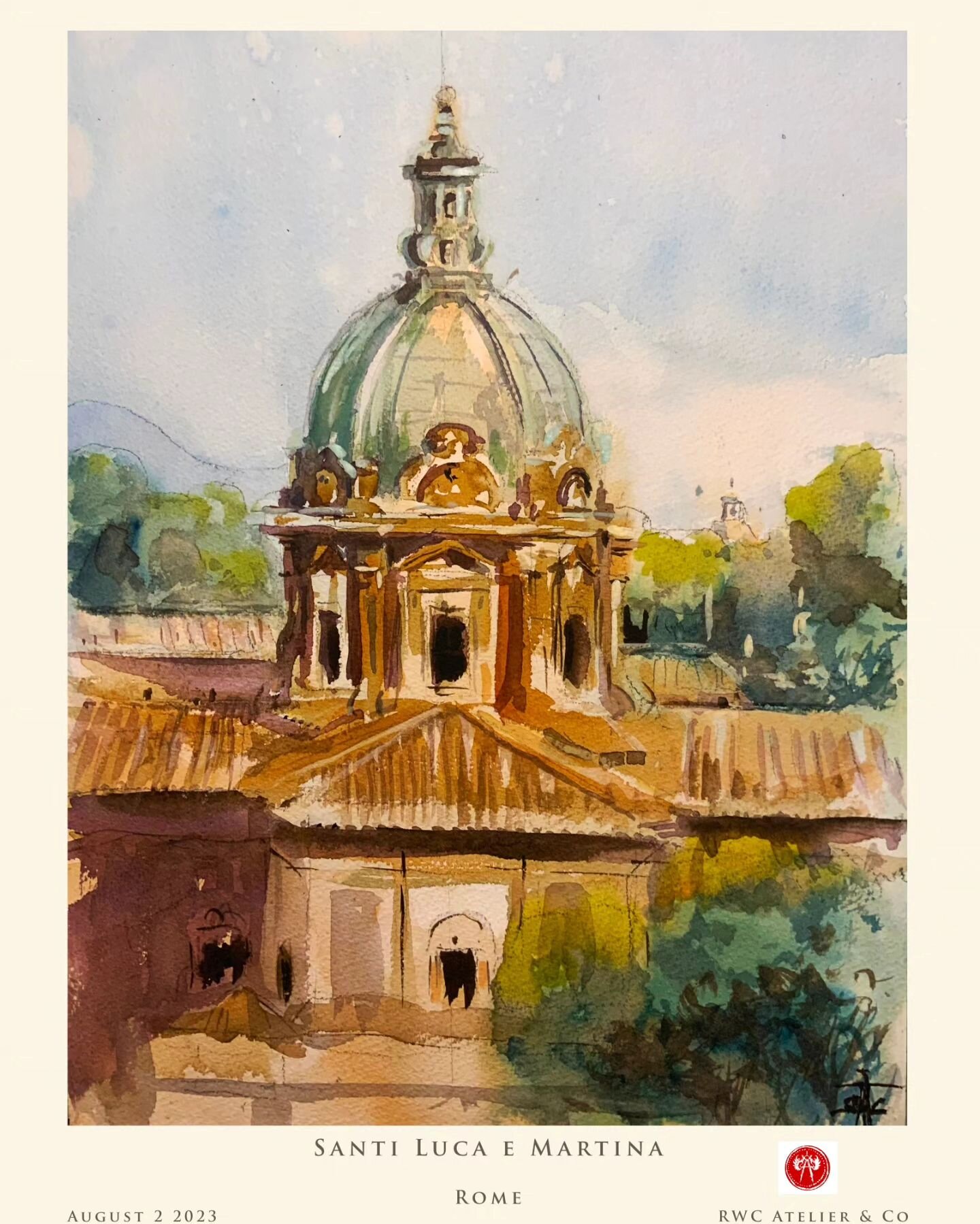

Pazzi Chapel, Florence, 1920: by Sidney Tushingham (Syracuse University Art Collection)

Having recently encountered and contemplated a few painted and photographed views of this famous work of Renaissance architecture, let's now take a closer look at the building itself.

First, the patrons: the Pazzi family were rivals to the Medici for much of the fifteenth century; theirs is a most astonishing, and sobering, tale of a powerful family's rise and fall.

A short introduction: The Pazzi conspiracy: The Scholar, the Prince and the Priest. And a bit more on the Pazzi Conspiracy and its aftermath: Part 1 ; Part 2 ; Part 3.

And here, a book on the story:April Blood: Florence and the Plot Against the Medici, by Lauro Martinez, Oxford University Press, 2003

Source

While some may be drawn to visit the Pazzi Chapel by the lurid history of its patrons, today most visitors come here for its architect. Innumerable Art History classes present this monument as the culminating work of the pioneering Renaissance master Brunelleschi, best known for realizing the dome of Florence's Cathedral, the Duomo.

A typical encomium to Brunelleschi's achievement at the Pazzi Chapel

A number of scholars, however, have begun to seriously question Brunelleschi's involvement here. New ideas were triggered when a thorough exploration of the fabric of the chapel, undertaken in the late 1950's and very early1960's, discovered a number of dated mason's inscriptions embedded in its mortar, giving us fixed dates for when the various phases of the building were built. These inscriptions date most of the core construction of the building to well after Brunelleschi's death in 1446.

The body of the building seems to have been begun at foundation level in 1442, when the chapel was consecrated on the fourth of July of that year. The plurality of the fabric was finished sometime after 1461, when building its dome began. The monument's ornament, what presents itself to our eyes today, was only being completed in the very year of the Pazzi conspiracy, in 1478! Also contributing to the mystery, an earlier facade was found hidden behind the present one, revealing that the familiar face of our building represents a substantial change of design in the final phases of the chapel's construction.

The most accessible scholarly book in English on Brunelleschi, by Eugenio Battisti, "Filippo Brunelleschi: The Complete Work", Rizzoli, 1981 republished in 2012), takes these discoveries into account. Thus, Mr. Battisti comes to the reasonable conclusion that, while Brunelleschi may have had a hand in the initial design of the work, the architects responsible for completing it were guided by Brunelleschi's already complete Sacristy for San Lorenzo, which the Pazzi Chapel closely resembles in many respects.

However, the new and indisputable evidence that the Pazzi Chapel was completed long after Brunelleschi's death opened the way for even more radical questions. The historian Marvin Trachtenberg took Battisti's conclusions to the next logical step when, in scrupulously studying the Pazzi Chapel through the lens of Brunelleschi's Sacristy, he concluded that the Chapel was a creative pastiche of the Sacristy by a distinctly different hand and mind: thus, not by Brunelleschi at all.

What these two buildings have in common is the motif of paired columns framing an arch. What had made the Sacristy for San Lorenzo radically new, however, in the context of its Late Medieval World, was foregrounding the Ancient Roman Corinthian Order as its primary architectural framework, and through this, ordering linked volumes that derive from the sphere (in other words, Roman vaulting). In the Sacristy there is a focused clarity of purpose and expression. This clarity is missing in the Chapel, where for example the columns-arch-motif (later popularized by Palladio) is applied indiscriminately, confusing rather than clarifying its complex intersection of volumes.

Trachtenberg made his case that the chapel is not by Brunelleschi in two articles, published in Casabella, a widely recognized Italian journal:

1. "Why the Pazzi Chapel is not by Brunelleschi", Casabella, June 1996

2. "Michelozzo and the Pazzi Chapel", Casabella, February 1997 (Free registration is required!)

Brunelleschi's late work does not revisit his earlier manner, as those who ascribe the Pazzi Chapel to him would have it. For Brunelleschi there are no "repeat performances". His Tribunes and Lantern for the Dome of Florence's Duomo are radically new, further forays deep into the world of the Ancient Romans, what his contemporaries called "all' antica", the "ancient manner". In this, and through their specific forms--scrolling volutes, layered elements, elisions, a sculptural three-dimensionality---Brunelleschi's late works prefigure the Baroque of two centuries later.

Here in the lantern, then, we encounter a work so surprising, and so "ahead" of Brunelleschi's own earlier Renaissance style, that it abruptly falls off the radar of pretty much everyone who studies Brunelleschi or the early Renaissance.

More on Brunelleschi's design for the lantern here:

So, why then did the Pazzi, these ruthless competitors of the Medici, ask their architect, Michelozzo, to conjure up a family monument so reminiscent of the Medici family monument? Perhaps, here is where our modern expectations deceive us. Perhaps it is the very differences between these two monuments, rather their similarities which were decisive? Perhaps it was not that the new monument was seen as reminiscent of the older one, but rather, that it was seen as better. At the very least, it was far more more complete, and certainly full of many more columns. Perhaps, then, it was that the Pazzi were announcing that they were far better at whatever the Medici were ostensibly good at.