Returning to Buildings Which Speak... Is this the key to Brunelleschi’s architecture?

by Michael Djordjevitch

Returning to the question of Brunelleschi’s architectural intentions (previously touched on in this Journal last July), could a key clue really be here, hidden in plain sight: staring at us (as it were) from deep within a seminal work of his greatest competitor and enemy ?

Is Ghiberti’s celebrated masterpiece, then, inadvertently revealing Brunelleschi’s artistic intentions? To resolve this question, we must first step back for a bit and examine a few more Renaissance works.

Mercifully surviving the vicissitudes of the twentieth century is one other sixteenth century Loggia in Pistoia, now the face of the city's Library and Archives, the Domus Sapientiae (Il Palazzo della Sapienza e la Biblioteca Forteguerriana). This monument was planned by Alessio d'Antonio, more widely known as Giovanni Unghero (1490-1546), in 1533 and completed by 1536.

The Loggia underwent a restoration between 1732 and 1743, giving us its current appearance.

Here the building speaks, though not quite as directly as does Pistoia’s Ospedale. There, as we have seen (post of July 17), it speaks through the figures of people in action. Here it speaks through the complex conventions of heraldic imagery. Further, and also unlike the Ospedale, it employs an ornamental and coloristic schema which creates an even middle ground against which the architectonic elements are disposed.

At the facade's center there is arrestingly present an elaborate cartouche, floridly displaying our institution's patrons and content. And through the art of trompe l'oeil it appears to emerge from that chromatic middle ground into the foreground of our attention.

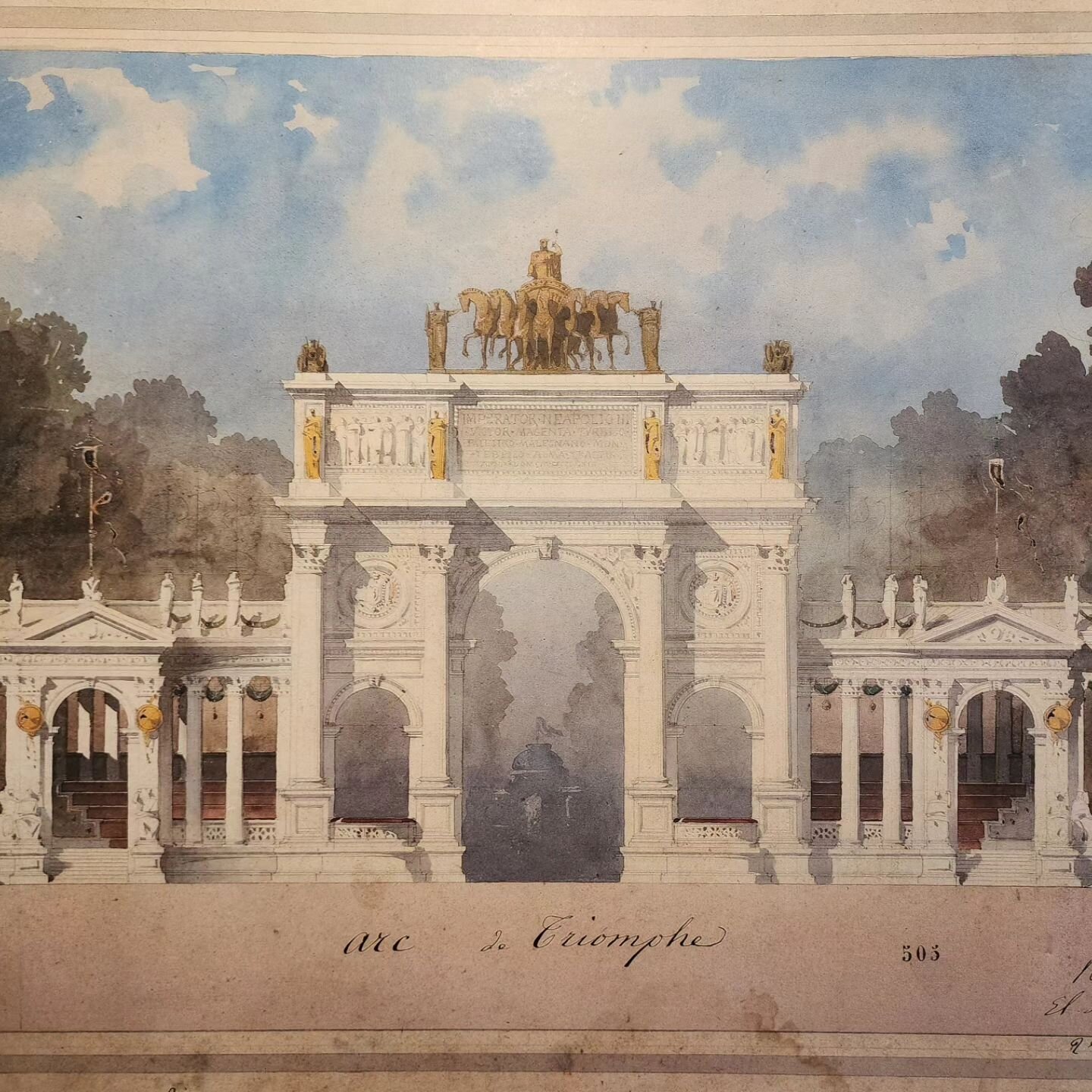

Within the archives of the Domus Sapientiae can be found the architect's original rendered elevation, documenting his absorbing design, one which through the the arts of symbolic ornament eloquently proclaims the House of Wisdom.

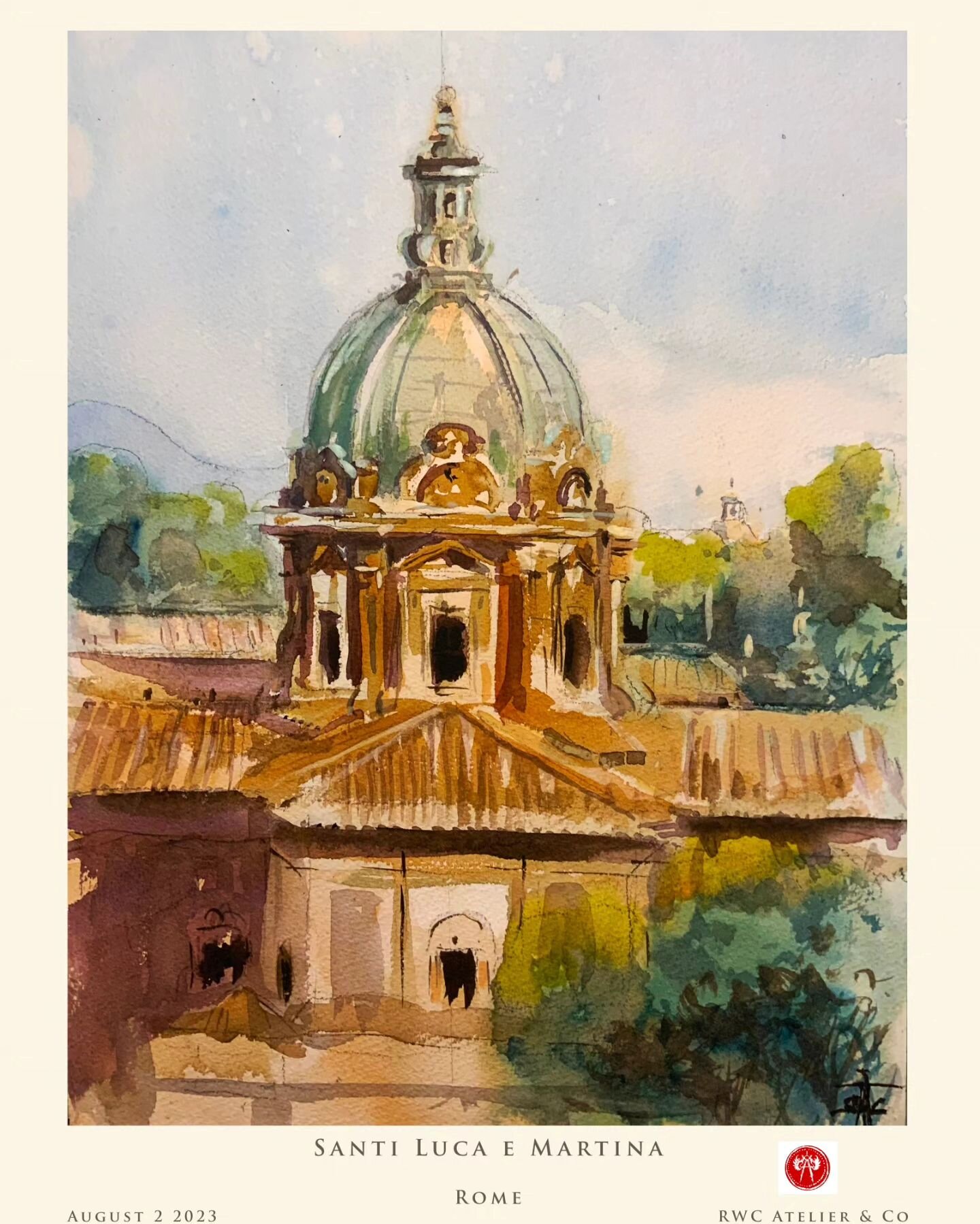

Contemporary with our building, and currently residing in the National Gallery, London, are a number of fascinating paintings of Loggias by an unknown painter who was active in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, now identified in the literature as the Master of the Griselda Legend. These paintings unambiguously show what finished loggias of the time were ideally expected to look like (for further instances see the post of July 28).

What is immediately apparent is the rich range of coloristic and ornamental possibilities which were at hand to artistically complete these works of public architecture.

Returning to Florence, and Brunelleschi's Ospedale degli Innocenti, what should be clearer to us now as a result of our explorations is how austere Brunelleschi’s facade is when seen in its culturally proximate context. Was the Ospedale then the work of a severe persona, and a pioneering proto-modernist work ?

To the contrary, when Brunelleschi took up the challenge of providing a design for the face of this new charitable institution, the Ospedale degli Innocenti, he did not propose a new architecture.

An earlier, though still near contemporary, Florentine building with a Loggia, once belonging to a late medieval convent and now housing the Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze (today immediately adjacent to the much visited {thanks to Michelangelo's David} Galleria dell'Accademia), offers us an illuminating comparison.

Much of the basic schema of Brunelleschi's facade, its type (its core design, as it were), is found here in this earlier loggia.

Yet, how this design is realized is the radical difference between the two.

That question of "how," is central, as it instantly becomes an issue of, from what, that is, from what elements is the design made from, or, in other words (Aristotle’s), the matter of its form.

This decisive difference in appearance, this change visible to all and sundry, this rejection of all that was then current in architecture, came to be expressed by Brunelleschi's contemporaries as his “Ancient Roman Manner": that all'antica character becoming Brunelleschi’s startlingly new contribution.

And yet, working with the elements of Ancient Roman architecture (and its associated arts), also brought with these a very particular set of relations, a new (to the late medieval) set of interrelationships between parts in terms of each other and the whole, and thus, a genuinely new Architecture.

To be continued …