Could this colorful, image-laden portico from the late fifteenth century today give us an insight into what Brunelleschi might have intended for his own first major architectural work, the Ospedale degli Innocenti in Florence?

by Michael Djordjevitch

This wonderfully vital building is the Loggia of the Ospedale del Ceppo, a Renaissance monument in the once-independent Tuscan city of Pistoia, northwest of Florence.

Well off the well-beaten tourist path, our Ospedale is easily recognized as a version of Brunelleschi's better-known Ospedale in Florence, and like that building this one too was once the public face of a charitable institution.

Founded in 1277 by a confraternity, The Companions of Santa Maria, the Ospedale del Ceppo was dedicated to alleviating the suffering of the poor. "Ceppo" (Latin cippus) refers to the hollowed-out tree trunk where, in times past, offerings intended for the poverty-stricken were left and collected. This Ospedale would become Pistoia's principal hospital following the onslaught of the Black Death in 1348.

Pistoia lost its status as an independent polity in 1401 when it was conquered by the hugely successful and rapidly expanding neighboring Republic of Florence. In 1456 the Ospedale del Ceppo invited one of Florence's most prolific and versatile architects, Michelozzo di Bartolomeo (1396 - 1472), to restore and expand its buildings. (For more on Michelozzo, see the entry from June 29, 2017) When in 1501 the Pistoian hospital was placed under the direct administration of the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova in Florence, its new directors commissioned a new facade whose arcaded loggia was intentionally modeled after Brunelleschi's for the Ospedale degli Innocenti in Florence.

The portico's prominent polychrome frieze, made of glazed ceramic, was created from 1525 onward by the Florentine sculptor Giovanni della Robbia (1469 - 1529), and his student Santi Buglioni (1494 - 1576), together with other members of their atelier. The frieze depicts the Seven Corporal Works of Mercy, which are visually separated by figurative representations of five of the Cardinal and Theological Virtues.

Source

The artistic style of these works is the fruit of the pioneering efforts of the brothers Andrea (1435 - 1525) and Luca (1399 - 1482) della Robbia, who famously developed and promoted the use of glazed terracotta for sculpture, and whose artistic impact can still be seen throughout Tuscany and beyond. Their vibrant and colorful glazes made their artistic products more durable and more expressive. By its third generation their atelier had committed itself to exploring a wider polychromic palette.

The Tondi below the frieze were sculpted at the same time by Giovanni della Robbia, here working alone. They depict the Annunciation, the Visitation, and the Glory of the Virgin, along with a number of coats of arms, that of the Medici unsurprisingly being the most prominent .

And thus this arcade speaks. Through the language of the figural arts it speaks symbolically, within the conventions of a cultural shorthand, but also directly, as even today we can see right before us charitable actions unfolding, such as people feeding the hungry or clothing the poor. These scenes are then separated by individual figures, allegories of the virtues, who through the specific objects they hold, and through their dress, signal their allegorically embodied meaning.

And do we not also see, when we look through the eyes of our two-and-a-half-thousand-year artistic tradition, something akin to the Triglyph-and-Metope frieze of the Ancient Greek Doric temple?

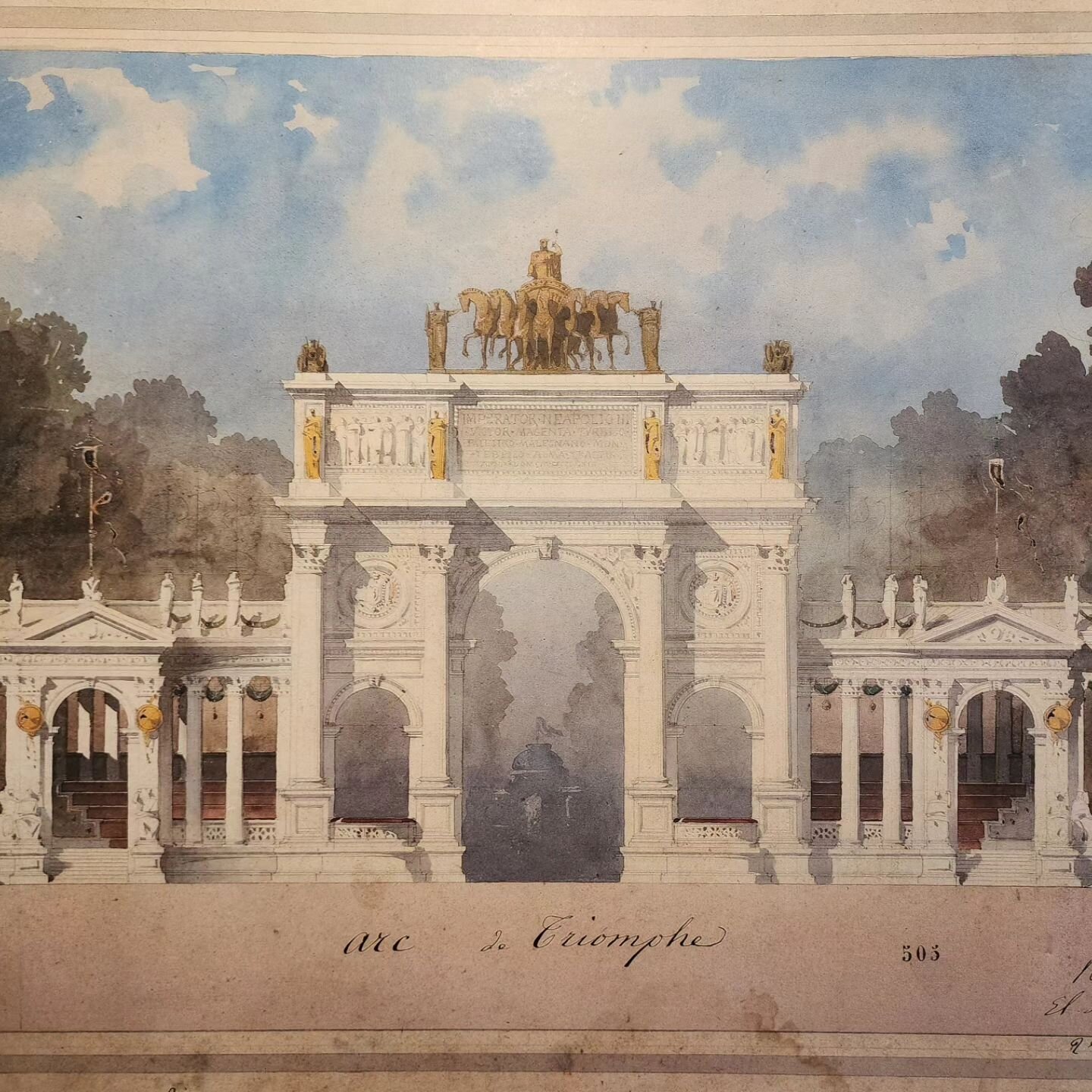

Also in Pistoia, there once stood, though only for a fleeting quarter century, another jewel of a building, the Loggia dei Mercanti, which took up and further explored the basic composition of the Ospedale loggia. The Loggia dei Mercanti, designed by Raffaello Brizzi (1883 - 1946), was begun in 1908 and finished in 1913, on the eve of the Great War, and it graced the city until its gratuitous destruction in 1939.

Here we again see, though more compactly, the syntax of our High Renaissance Pistoian Loggia with its division into framed and sculpted panels, and the same fruitful union of sculpture and architecture. Here then is an example of the long-lived momentum of a vital artistic culture stretching back to the Renaissance, and though we are separated from it by decades of modernist design practice, this artistic culture still remains intelligible to us to a considerable degree.

In later postings we will briefly return to this recent Pistoian Loggia, and also turn to the one other surviving Renaissance Loggia in this Florentine colony with extensive ornament. But next week we'll take a look at a number of paintings to illuminate Brunelleschi's likely intentions for his revolutionary Loggia in Florence.